The annals of world cinema are replete with examples of teaming ups between an actor and a director. From F W Murnau and Emile Jannings, Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune, Ingmar Bergman and Max von Sydow, Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood, John Woo and Chow Yun-Fat, Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski, John Ford and John Wayne, Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro, Steven Soderbergh and George Clooney; to our very own Satyajit Ray and Soumitra Chatterjee, Manmohan Desai/Prakash Mehra and Amitabh Bachchan, and Karan Johar and Shahrukh Khan—the list is always a work in progress. Equally rare are instances of director duos, who are not siblings. Johnnie To and Wai Ka-Fai from Hong Kong belong to that sparsely populated elite club of collaborating directors, who are filmically, and not fraternally, connected to one another.

Another interesting aspect of the To-Wai collaboration—as many as eleven out of the seventeen films that Wai has directed till date have To as co-director—is that more often than not, the films have had a supernatural element woven into the plot. Cases in point are: My Left Eye Sees Ghosts (2002), in which a young woman develops the ability to see ghosts after a car accident and Running on Karma (2003), where a monk-turned-bodybuilder finds he has the power to look into people’s lives.

As the opening credits of San Taam (2007) a.k.a Mad Detective—their latest outing together—start rolling, with all the letters appearing in an angular manner, we get the first impression that what is about to follow will be anything but straightforward. That feeling is fortified when we are introduced to the titular character, an inspector of West Kowloon’s District Crime Division, Chan Kwai Bun (portrayed by Lau Ching-Wan—a favourite of Johnnie To, who has featured in several of the director’s films, including A Hero Never Dies [1998]; Where a Good Man Goes [1999]; and Running out of Time [1999]).

Many films have a character who acts as a proxy or surrogate for the audience (Ariadne in Nolan’s Inception, for instance). In San Taam, inspector Ho Ka-On (played by Andy On), a new joinee in Bun's department, acts as the audience’s eyes and ears. It is via him that we are introduced to the oddball Bun, who, we are told is in the middle of an investigation that involves cracking the case of a student’s body being found inside a suitcase. To the utter dismay of both us and Ho, Bun climbs into a suitcase and requests the greenhorn detective to zip it and push it down the stairs. As soon as the suitcase reaches the end of the staircase, out emerges Bun, screaming ‘The ice-cream shop owner is the killer’, as if struck by an epiphany!

Flashes of newspaper headlines make it amply clear to us that irrespective of how zany and unorthodox his methods are Bun has an excellent record in solving criminal cases. But unlike other times, when his colleagues actually requested him to put his uncanny knack for the unconventional to use, the department decided he had gone too far the day he offered a farewell present to the retiring chief that—for want of a better term—can only be called ‘Van Gogh-ish’.

Five years pass by. Banished from the force, one day, the loon from Kowloon finds a visitor at his doorstep. It is none other than Ho. Initially reluctant to even speak with Ho, Bun’s interest gets piqued when Ho tells him that even though he had worked with him for only two days, he considers Bun to be his idol. In fact, when Ho’s gun developed a defect, he was given a new one—Bun’s. And it is a gun that forms an integral part of a case that Ho is now in charge of—a case in which he wants Bun’s help.

The extent to which Bun’s nickname suits him becomes apparent once he revisits the department that he was once the pride of. During the briefing session on the case for which his assistance has been sought, both Ho and us get to learn that Bun has a special ability—that of seeing the inner demons of a person.

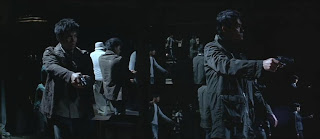

It is here that To and Wai have displayed their finesse as filmmakers. What Bun sees in a person is different aspects of the same self, but as separate individuals—can even be of different sex—each with distinct nature and objectives. While this preposterous plot point is taken with more than a pinch of salt by both Ho and us, gradually, as the film progresses, we warm up both to this suited-booted-sans-socks oddity and his frequent ‘visions’.

And just when we find ourselves at ease with Bun’s philosophy (‘Apply emotions to investigate, not logic’) and the methods behind his madness (which includes using his index finger as a pistol as he recreates each crime scene, a request to be buried alive, and ordering the same dishes again and again at a restaurant), like master storytellers, To and Wai plant a seed of doubt in our minds. We are left to wonder if Ho’s quirkiness is nothing but evidence of a mind in complete disarray.

While some of us might point out ‘The more complicated the story, the better for us’—a line spoken by a character in San Taam as a description of the film itself; especially in the context of the convoluted climax that is equal parts The Lady from Shanghai (1947) and Enter the Dragon (1973), the film is a success in the sense that it makes us question where exactly sanity ends and insanity begins—a point brought to the fore by the translation of the film’s title. The literal English translation of San Taam is ‘godly detective’, while the international title is ‘mad detective’ proving once again that there is indeed a very thin line between being a seer and being sneered at.

No comments:

Post a Comment